Tagged: Holocaust

Corporate Responsibility

Last year while helping to put together a travel guide on Berlin I wrote a review about this memorial. It’s a clever little space occupying a dark corner of the tourist trail only a short stroll from the Brandenburg Gate. Undulating pathways rise and fall through the 2711 concrete blocks; but gradually towards the centre the path slopes lower and the blocks begin to rise above you. It gets dark. The width of the pathway has been designed to only allow for one person to walk down at a time and you quickly find yourself alone. Your friends become lost amongst the blocks as they take their own path, and you catch glimpses of the others as you make your own way to the other side. The design is simple and effective, it works on both a visual and emotional level and certainly made me think – I thought it was a worthy memorial. However, as I began to conduct some research for my review I discovered a mammoth controversy surrounding the project. A company called Degussa was involved in the estimated 25 million euro construction process, providing the anti-graffitti for the ‘stelae’ concrete blocks. It just so happened that the collection of companies that Degussa belonged to (under the wartime umbrella of the behemoth IG Farben) had been responsible for the production of Zyklon B – the pesticide used in the gas chambers. All work on the memorial ceased while a decision was being made on Degussa’s involvement. Despite much criticism from the Jewish community and journalist Henryk M. Broder commenting that “the Jews don’t need this memorial, and they are not prepared to declare a pig sty kosher” the board of directors decided to continue building with material from Degussa. The argument for this was that it would have been ‘impossible’ to exclude companies who had collaborated with the Nazi’s as German politician Wolfgang Thierse stated, “the past intrudes into our society”. No doubt financial constraints also influenced decisions.

The controversy surrounding the Holocaust memorial (as it is often referred to) left a bitter taste in my mouth. In no city that I have ever visited has the past ever intruded so much as it does in Berlin. No matter where you go the war and the wall have a way of creeping into your conscience; history is everywhere. I read some arguments suggesting that it was fitting that Degussa should take part in building a memorial as acknowledgment of their past and reparations for their part in the Holocaust. But hold on just a minute; Degussa got paid for their construction work, they didn’t offer it as a too-little-too-late goodwill gesture. Nor did they bid for the contract with the aim to make amends, I’m sure they hoped that in the mess of subsidiary companies, and merged companies, and disbanded companies – plus several decades – their connection to the gas chambers might be overlooked.

At the moment I am working for a German chemical company which was one of the collection of companies which merged in 1925 to form IG Farben, which collaborated closely with the Nazi’s before being disbanded for war crimes in 1945. IG Farben held the patent for Zyklon B. It used slave labour from concentration camps in the manufacture of materials for the armed forces, most notably the Buna synthetic rubber factory at Auschwitz. A number of employees were prosecuted for war crimes. Understandably IG Farben was not allowed to continue to exist after the war, however, the original founding companies were quickly reestablished under their old names and continue to exist to this day. And I am working for one of them.

It surprised me to learn that actually quite a lot of well known companies have a brush with the Nazi’s, although come to think of it – if a German company pre-dates 1939 it’s likely that they’ve had a tryst with party one way or another. Kodak used labour from camps, so did Volkswagon and Siemens. Hugo Boss got a contract to produce SS uniforms, and the parent company of Random House, Bertelsmann A.G, published Nazi propaganda. So cameras, cars, clothes. But I’m part of the company that has Zyklon B languishing in its back catalogues, no matter how much they try to sever the tie from IG Farben. Over the past few months that I have been working there this subject has been on my mind quite a bit, which has prompted me to dig deeper. Surely, I thought, this company must have issued a formal acknowledgement and corporate apology for its prominent role in mass murder – and in order to satisfy my uneasy mind it was necessary for me find this apology. But no such apology exists.

On the company website there is a detailed run down of the long history of the company, from it being founded pre WWI to the IG Farben merger and the reestablishment of the company after the war – and up to the present day. There was a little bit of information about use of slave labour at the Buna factory, but absolutely no mention of Zyklon B, let alone anything resembling an apology. The company has skipped over this, expunged it from the records – and they are not alone. Several other ex-IG Farben companies, and these are very big multi-nantional companies with turnovers running into several billion euros, have also not apologised for their collaboration with the Nazi’s. I find this deeply disappointing, and I have lost a lot of respect for the company I am working for as a result. I appreciate that the Holocaust is a period in history which they would rather gloss over as obviously it is a terrible business association, but an apology would gain my respect, and an apology is what I would expect from any company after involvement in something so awful. The company I am working for has a set of ethical guidelines outlining a long list of things it will not take part in today – however, without an apology for the past these guidelines are a mockery. How can we be sure that they won’t participate in chemical warfare the next time around? In my opinion these companies should not have been allowed to reestablish themselves under their old names as if the Holocaust had not happened. With German infrastructure so delicate after the war it would have been cruel to completely bulldoze what was left of these chemical/construction/medical companies as they were much needed to rebuild the country. However, I do think they should have been forced to properly rename and reform as entirely new companies, with no link to the past.

At the opening of Berlin’s memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe, Holocaust survivor Sabina Wolanski emphasised that the children of the perpetrators of the Holocaust were not responsible for the acts of their parents. While the employees of today are not responsible for the acts of the past, the companies still are. It is not too late to apologise, and I’m sure I won’t be the only one waiting.

Small frightened animals

6 million is the figure that springs to mind first when I start thinking about the Holocaust, but try as I might I can’t seem to find exactly where this figure comes from. Conservative estimates range from just under 6 million, right up to a staggering 26 million depending on your definition. What’s fairly certain though is that these figures don’t include those who died indirectly as a result of the Holocaust years, or maybe even decades later. The suicides. The broken hearts. Nor do these figures give any idea of the number of people who struggled with the fall out of the Holocaust to the end of their natural lives, often having an impact on their children and loved ones.

In 1992 American cartoonist Art Spiegelman won a Pulitzer Prize for his graphic novel, Maus. Spiegelman interviewed his father Vladek, a Polish Jew who survived Auschwitz, about his experiences with the aim of turning them into a graphic novel. Tricky stuff this, the Holocaust doesn’t really lend itself easily as a subject for a cartoonist. Spiegelman made the decision to portray the characters in the story as animals, the Jews are mice, the Nazis are cats, and the Americans are dogs. There is no human or sub-human here, just small animals helping or terrorizing each other arbitrarily.

What is fascinating about Maus is that is more than just the story of Vladek’s experiences during the war. Maus becomes the story of how the Holocaust continued to effect him even as an old man in America, and how this in turn had an impact on Art Spiegelman himself. Vladek’s foibles are want to drive his young son insane, he is stubborn, tight fisted with money to the extent that Art complains his father fulfills the stereotype of the money grabbing old Jew. Vladek is unable to see any little useless thing go to waste; picking up bits of wire off the street, trying to return opened boxes of cereal to the supermarket. Added to all of that is the nightmares and the sadness, even after surviving Auschwitz and losing their first son in a ghetto liquidation Vladek’s wife Antje committed suicide in 1968.

Suddenly it becomes clear that the legacy of the Holocaust outlasts its original victims. Art Spiegelman himself spent time in a mental institution, dealing with his own problems, but no doubt with those of his parents looming large. Maus is more than just a graphic novel to entertain and educate, it’s a book that helps to get out the story of the children of the survivors, and for Art Spiegelman surely a form of therapy to deal with his troubled family history.

Night and Fog

Ok, so three days before Christmas is probably an unlikely sort of time to be reviewing a Holocaust documentary. I really ought to be munching on mince pies and offering my views on The Hobbit or something. However, I’ve been meaning to watch Night and Fog for ages (since September) and I thought as I’ve already mentioned Alain Resnais this week I might as well run with that.

The Holocaust has loomed quite large in my sphere of consciousness this year. I spent a month in Berlin during which time I visited a concentration camp and wrote up the experience for a travel guide, as well as writing up both the Jewish Museum and Peter Eisenman’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. I was morbidly fascinated with the Holocaust when I was younger (I read the Diary of Anne Frank when I was 11 and it snowballed from there) but it didn’t occur to me until this year that even though I might have learnt a lot about the Holocaust I still didn’t ‘get it’. I still don’t ‘get it’, and I believe that unless you’ve been through it then you never will.

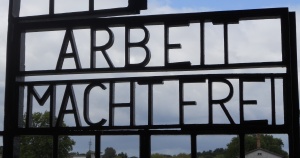

But boy, since wandering around Sachsenhausen concentration camp on my own do I have a better idea, and I have to tell you I’m not really pushed to dig a lot deeper. I always wanted to visit Auschwitz, but hey, now I’m really not sure about that, I think I’ve done my concentration tourism – and it was certainly enough. Anyhow, I got into conversation with one of my friends about this whilst in Berlin and he recommended Night and Fog, so here I am.

I already like Alain Resnais, but how would did he deal with such a sensitive subject?

Bearing in mind what sort of thing Resnais would go on to produce it is interesting that images in this film appear so surreal. Surely with that box full of human heads and bulldozer clearing away bodies we are looking a work of fantasy, something from a different world? But no, not this time.

Night and Fog was produced in 1955, a ridiculously short amount of time after the war. I think this might actually be the earliest documentary about the Holocaust I’ve ever seen, and it’s certainly the most shocking, no surprise that it ran into censorship problems. The film switches between archive footage and contemporary views of Auschwitz, faint of heart beware – this is graphic, and it’s absolutely brutal.

‘Night and Fog’ is a poignant title, drawing attention to the shady handling of prisoners by the German military. Millions of ordinary people were plucked out of their lives, sent off to the camps and ‘disappeared’. I’m not sure how I feel about this, so the mechanics of the camps were kept secret – but what did the people really think happened to those prisoners? In Oranienburg (the sleepy suburb where Sachsenhausen is located) residential houses run almost up to the front gate. Thousands of people go in, no one comes out, and still more people keep coming. It’s pretty obvious what’s happening. Or is it? That section of life between arriving at the camp and death is where the real cloak and dagger horror is; the starvation, the miserable conditions, death leering at every corner. So giving the film this title is like a attaching a billboard to the whole thing, calling out the Nazi’s on their great cover up.

The script was written by camp survivor Jean Cayrol, no doubt an almost impossible task. The narrative is measured and poetic without being bitter or condemning, there is a sense that Cayrol and Resnais are just presenting the facts and it is up to the viewer to draw their own conclusion about who is responsible. As the camera spans over the tumbledown, now peaceful ruins of Auschwitz there is a plea not to forget, not to let it happen again.